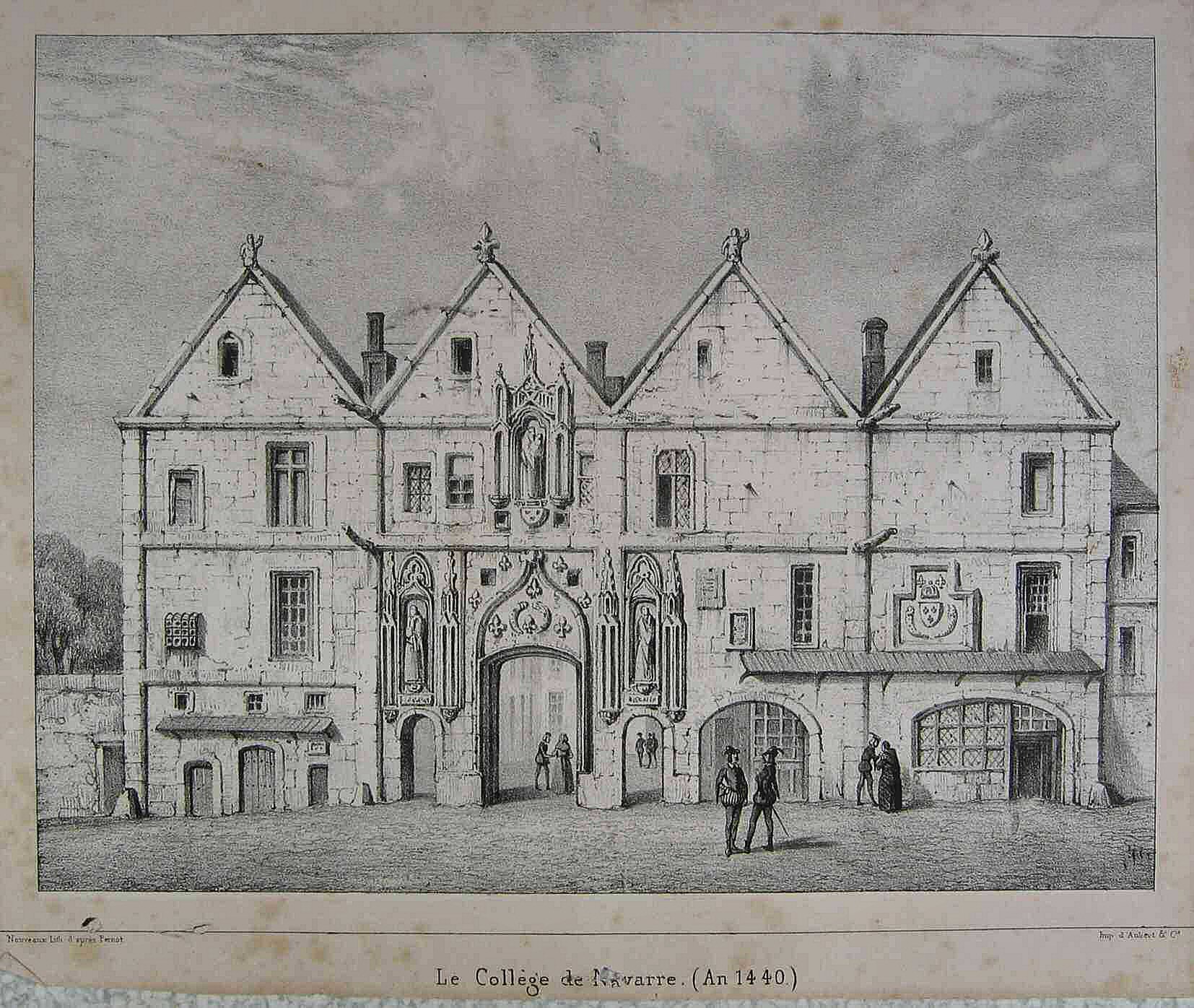

Collège de Navarre

Some of the most strikingly gendered instances of reginal patronage in the first third of the fourteenth century are the foundations of the Collèges de Navarre and Bourgogne–endowed by women, for men. The Collège de Navarre was erected between 1309-1315 under the testamentary orders of Queen Jeanne de Navarre et Champagne (1273–1305), wife of Philippe IV (1268-1314) (figs. 9–12) [Place Ills. 9–12 here].The second was also built according to the wishes of a deceased queen–Jeanne de Bourgogne et Artois, daughter-in-law to Jeanne de Navarre, and wife of Philippe V, discussed above, and it was dedicated in 1333. Both colleges were erected on lands purchased with funds of the queens, situated south of the river in the university quarter. Their locations in the heart of a district that was traditionally patronized only by men is significant in itself. That these edifices displayed female support of education on such a monumental scale adds to the innovative nature of the commissions. A mother’s role in the education of her children was one that these queens’ saintly and learned ancestor, Louis IX, had frequently espoused, learned in large part from the actions of his own mother, Blanche de Castile (1188-1252). And yet these colleges were the first two manifestations of that duty of the queen, in this case to the nation of France rather than just the royal children, that we find expressed architecturally in the city of Paris.

Still another remarkable aspect of the location of these colleges lies in their close proximity to the primary tombs of both these queens, neither of whom chose to be buried next to their husbands in the royal necropolis of the monastery of Saint-Denis. We argue that in an era often seen as one in which the power of women had declined, women of the French royal court gained access to public life through the ceremony and patronage intrinsic to such architectural commissions, thus making their public identity permanent in both the building’s design and the urban landscape. The siting and design of these buildings reveal women’s hands in their creation and how that vision fits into the larger physical and ideological topography of the city of Paris. Important themes emerge that associate Jeanne de Navarre and Jeanne de Bourgogne with the ideal queen as promoted by Capetian ideology–namely, service to her people–while co-opting a form that had traditionally been reserved for the male world–the large-scale educational complex.

The funding of these colleges demonstrates how women marked the landscape as their own. Both women used proceeds from the sale of their personal familial hotels to fund their projects. The Hôtel de Navarre was located on the rue Saint-André-des-Arts, near the porte de Bucy and the porte de Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Jeanne de Navarre had kept a separate household from her husband’s and resided in the hotel of the kings of Navarre when in Paris. Jeanne de Bourgogne had inherited her hotel, known as the Hôtel de Nesle, before she was queen when she and Philippe were still just countess and count of Burgundy. It was to this residence, located on the banks of the Seine in a tower of the city wall, that she retired after her husband’s death in 1322. In later years, both hotels were described as two of the most lovely residences in Paris, a fact that allowed these queens to fund their foundations for the most part from their sale. The rest of the money needed to keep the colleges running thereafter came from rent on lands in Champagne and Brie, and Burgundy respectively.

Present-day location: 5 Rue Descartes